We’ll talk here about the best inventor software on offer for use in different steps of the invention process.

Brainstorming Inventor Software

bubbl.us

bubbl.us is a free and very easy to use online mindmapping service. Within minutes you can have a nice looking and multi-leveled mindmap. You can also save, print, import and export your mindmaps for modification or future reference.

Microsoft Visio

We’ll speak about Microsoft Visio in more detail in the Patenting Software section below. Besides 2D design work, Visio can be used for mindmapping and brainstorming, and thus is great for the creation and ideas phase of the invention process. It allows you to build keyword hierarchies in an easy to use and organized manner, and moreover lets you order them and re-organize them if necessary. The advantage of using Visio as opposed to, say, just sketching a mindmap, is that you can always come back to your brainstorm and modify or re-engineer it at a later stage.

SmartDraw

SmartDraw is an excellent piece of software which we’ll talk more about below, and it works in similar fashion to Visio for brainstorming purposes. Check out some SmartDraw brainstorming examples to see how easy it is to brainstorm and mind-map with it.

Inventor Software For Sketching

In this section we’re going to look specifically at tablet apps. Tablets such as the iPad have become incredible tools for inventors, as they allow you to sketch ideas on the go using powerful sketching software.

Sketchbook Pro

Sketchbook Pro is one of the best iPad and Android apps out there for invention and idea sketching. It provides multiple types of digital pencils, brushes, markers so that you can freely sketch your ideas and innovations in a way that works for your needs.

Check out this video to give you a good overview of how Sketchbook Pro works:

Paper by FiftyThree

Paper is another amazing sketching app that focuses on simplicity and a provides a minimalist design interface. It allows you to organize your sketches into digital ‘books’ in a very cool and effective way. Use it if you like to make lots of quick sketches: it beats a physical sketchpad any day.

Invention Product Design Software

Google Sketchup

Google Sketchup is a simple yet powerful piece of 3D modeling inventor software, and the free version is a brilliant way for inventors to start modeling their designs into 3D objects. Some of its features include conversion of 2D designs into 3D, exact measurements for prototyping and production purposes, grouping and ‘clipping together’ of distinctly designed components, texture and color surfacing, animations and presentations of designs and even a feature to cut away and go inside a design.

Google Sketchup comes with lots of free training videos (as well as real-world training), and here’s an example of one to see how it works:

AutoDesk Inventor

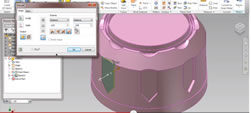

Inventor software AutoDesk Inventor is a state-of-the-art 3D CAD design system that allows you to design, control and even simulate your inventions before building produce physical prototypes (sometimes even preventing the need to product a physical prototype). Its numerous features include converting 2D CADs into 3D, assembly design, motion simulation and mold design. It also comes with video tutorials that guide you through all features of the inventor software package.

AutoDesk Inventor software comes in different versions and different prices, and it’s one disadvantage is that it’s quite pricey (from $999 onwards). However if you use it to its full capabilities, and put in the time to learn how to use all its features, it’s worth the price. Take advantage of the free trial if you want to test it out.

Here’s a very long but very comprehensive demonstration of using the invention software to design an LED Lamp:

Patent Design Software

Microsoft Visio

If you have a PC with Windows installed, one of the best patenting design software you can get is Microsoft Visio (available in both standard and professional versions). Visio is a very powerful design tool, which is primarily used for 2D design work. As a result it allows you to draw up virtually anything that would be required for 2D patent document diagrams. This includes patent diagrams, flowcharts and scenario charts. Visio allows anyone to build professional looking designs using existing templates and pre-drawn shapes. For the most part you can do these designs without requiring the services of a professional draughtsman.

If you are wanting to get to grips with patent designing, particularly when using a design tool like Visio, it always helps to do a patent search.

Here’s a Visio demonstration video:

SmartDraw

SmartDraw is the non-Microsoft equivalent of Visio, and some people prefer it because it is an independent company and regularly updates its software (Visio has much longer product cycles). It can do virtually everything that Visio can do in terms of 2D design work, and includes hundreds of templates and pre-designed shapes. In other words its a great piece of inventor software, and allows you to come up with professional looking designs without having to be a professional designer.

Here’s a SmartDraw demonstration video that will give you more of an idea of its capabilities:

That’s it for now folks. Come back to see updates and new inventor software as it becomes available. Good luck!

It’s not a cliche, nor is it some kind of marketing gambit, to say that anyone can be an inventor. Learning how to be an inventor is a process just like learning how to ride a bicycle or learning how to draw. Some people say that you need some special kind of ‘talent’ to draw, that it is innate and that you can’t ‘learn’ it. Yet many books, courses and educators have

It’s not a cliche, nor is it some kind of marketing gambit, to say that anyone can be an inventor. Learning how to be an inventor is a process just like learning how to ride a bicycle or learning how to draw. Some people say that you need some special kind of ‘talent’ to draw, that it is innate and that you can’t ‘learn’ it. Yet many books, courses and educators have

An invention timeline can be described as the path that takes a new process or product from conception to realization. An invention could be based on improving earlier ideas or could be something completely new and unthought of.

An invention timeline can be described as the path that takes a new process or product from conception to realization. An invention could be based on improving earlier ideas or could be something completely new and unthought of.